by Craig Klugman, Ph.D.

The FDA has approved the world’s first gene therapy: Luxturna (voretigene neparvovec; AAV2-hRPE65v2) is a one-time intervention that can treat an inherited retinal disease (RPE65-mediated inherited retinal dystrophy). The disease is rare, affecting only 1,000-2,000 people in the U.S. The treatment works by introducing a virus to the eye that contains a healthy copy of the gene that caused the blindness. In a phase 3 trial of 31 subjects (20 intervention; 9 control; 2 withdrew), 65% of patients who received the procedure experienced dramatic improvements in their vision. While patient’s do not develop “normal” sight, they can see far more than was possible before the gene correction.

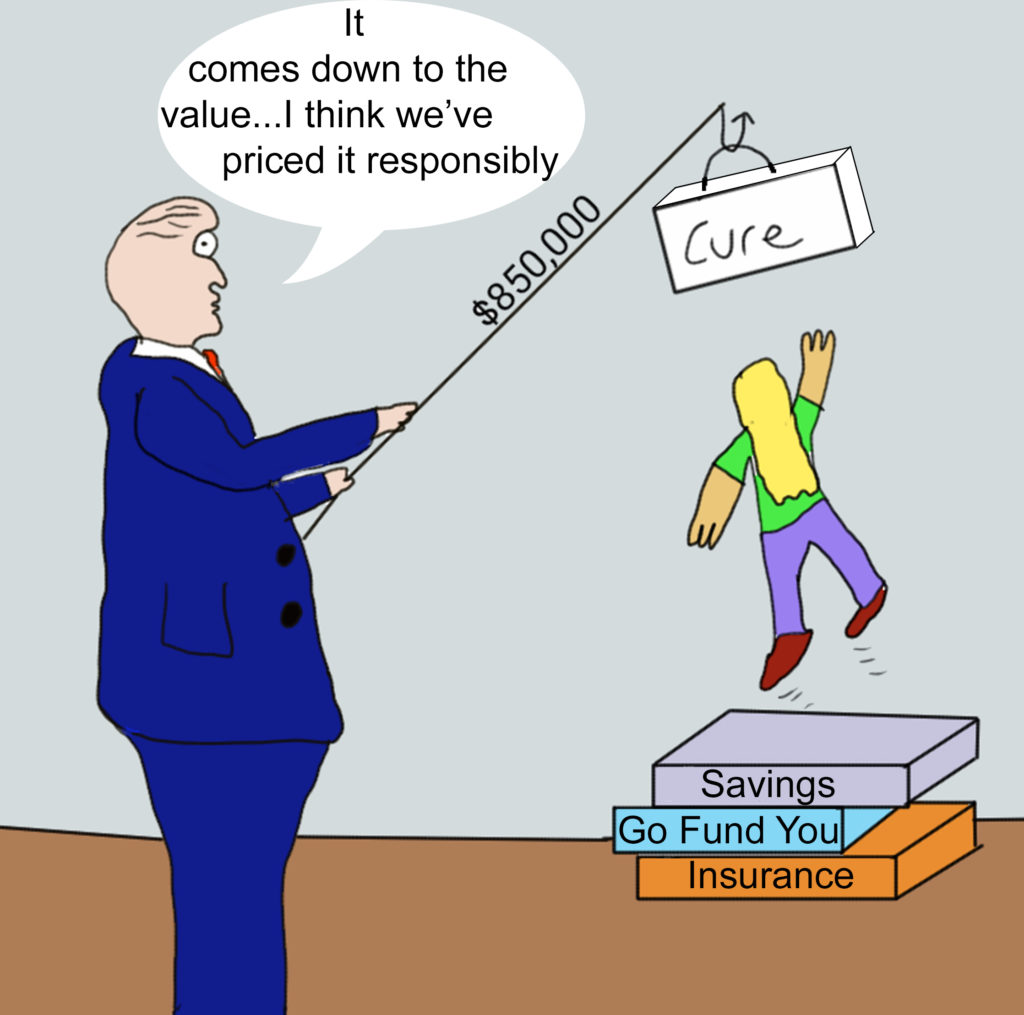

This treatment may herald a coming age of gene therapy that offers medical miracles to patients. But such marvels come with a price, in this case, an $850,000 price tag. Wall Street considers this price to be a bargain since they expected such treatments to be priced at closer to $1 million. According to the manufacturer’s—Spark Therapeutics—CEO, “It came down to the value we believed was inherent in the therapy.” The CEO admits that the price was not based on the cost of research and development, or the cost of delivery, but rather at what the company perceived as the interventions “value.” In other words, what they thought people pay for it.

The trend of releasing drugs at a high price point and then pushing it even higher is a recent trend in the pharmaceutical industry. The most prescribed medication in the U.S. is Humira, which retails for $38,000 a treatment. The price was raised 9.7% this month alone (total U.S. inflation rate for 2017 was 2%). Even with insurance, out of pocket payments can approach $1,200 per treatment. Medications in the U.S. tend to be higher than other developed countries that have an organized health care system which can negotiate for lower prices. The high price of medication is usually blamed on the cost of research and development and clinical trials required by the FDA for market approval. However, a 2016 JAMA study found that high prices are a result of drug company monopolies and coverage requirements on government insurance plans: “Although prices are often justified by the high cost of drug development, there is no evidence of an association between research and development costs and prices; rather, prescription drugs are priced in the United States primarily on the basis of what the market will bear.”

Consider that the development of voretigene neparvovec was funded by several non-profit sources. The Foundation Fighting Blindness is a non-profit founded in 1971 to research cures for blindness. They offer grants to researchers, fund clinical centers and disseminate information. FFB claims to be the largest private funder of blindness research. The two main researchers that developed voretigene neparvovec as a clinical intervention both received career awards from FFB, which allowed them to compete for National Eye Institute Grants. In addition, the researchers received $4 million from the NIH to support their research efforts at the University of Pennsylvania’s Childrens’ Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP).

So how does a treatment that was developed with private non-profit foundation and NIH funding end up being offered for close to $1 million a patient by a for-profit corporation? Like many researchers in the clinical translational model, the researchers founded a private company, Sparks Therapeutics, and licensed the technology from the university. In this case, the license is held by CHOP, Penn and the University of Iowa Research Foundation. In fact, CHOP is one of the largest stakeholders in Sparks. Luxturna is currently their only product though they plan to develop more gene therapies. According to SEC filings, Sparks claims to have lost $53 million in the first quarter of 2017, nearly twice what it lost in 2016.

This investigation leads to the question of whether this treatment can be ethically sold at such a high price. Clearly, the price tag means this treatment violates social justice—it can only be afforded by those with the means to pay for it. One must also consider that blindness itself is a social determinant of health as people with blindness statistically have lower income than their seeing peers. Sparks is working with a limited number of insurers to cover the procedure and those insurers will have their money refunded if the treatment fails to work. How many insurers would be willing to cover this therapy and what co-pays they may demand are not yet known. Sparks has also offered a payment plan: Like a mortgage, people can purchase the treatment and then pay for it over time. The pharma industry’s concern is that unlike chronic disease where one can be paid by patients and insurers over a long period of time, gene therapies are often a one-time use, meaning a one-time fee. Thus, new payment models have been proposed to keep a more dependable, and long term, source of income from payments. Still, many people will be unable to afford a therapy that costs more than the average American house ($272,900 in 2010-Census.gov) and more than a college education ($168,000 tuition; $204,000 tuition, room, board, books, fees for 4 years at a private nonprofit college-collegeboard.org).

If indeed the cost of gene therapies is going to be at the $1 million mark because that is what the market will bear, that leaves the U.S. with some difficult decisions:

- Allow the free market to rule and people can afford these treatments or who have insurance that covers the cost can have the treatments

- Include cost of the drug as part of the FDA review and not allow to market any drug that would cost more than a set threshold.

- Not pursue gene therapies. There is something to be said for the idea of not pursuing therapies that will (a) only affect a small number of people and (b) is unavailable to most people. Given that public dollars are used in this research, do these investigations lead to the greatest reward for the greatest number?

- Permit and encourage the federal government to negotiate with Sparks (and other future companies) to purchase the drug at a highly reduced (bulk) rate and then re-sell the treatment to hospitals and patients for the reduced price. Or allow insurers and hospitals to negotiate for lower prices. Currently, it is illegal for federal health plans to negotiate pharmaceutical prices so this would require a legislative change.

- Create gene therapy insurance plans. Given these costs, any insurance plan that covers them will have to increase premiums and have special co-pays for these high dollar interventions. Thus, perhaps separate insurance plans that cover only gene therapy would be offered. The problem, of course, is that the only people who would purchase these plans are those who need them, meaning premiums could be almost as high as the cost of treatment without insurance.

- Offer discounts to tax payers for drugs developed with public money. Voretigene neparvovec was developed as a treatment, in part, with federal grant money—money that comes from the taxpayers. Why should people who have already paid into (in very small part) this drug pay again to receive it? Perhaps for anyone who paid U.S. taxes, there should be a discount. This would be like the city-resident discount I receive at local museums that receive grants from the City of Chicago. The thinking is that since my tax dollars go toward supporting the institution, I get a small discount on my visit.

- If, as a society, we agree that gene therapy is a good, then perhaps we need to create a federal program to help subsidize gene therapy. The federal government pays most costs associated with patients treated for end-stage renal disease. At the time that the technology was made available, no one wanted to choose who could get the treatment and who could not, so Congress chose to just pay the costs out of federal coffers. As a nation, we could decide to do the same for gene therapies. The problem, of course, is that the high prices mean we would have to go well beyond having 17% of our GDP go to health care and there would necessarily have to be increased taxes (especially after just cutting them so dramatically that is burdening all social services).

- Require conflict of interest fiduciary rules that do not permit researchers and institutions who received federal grants to develop interventions to use those publicly funded goods for personal gain. In other words, researchers could not be officers or major shareholders in companies they create simply to market and distribute drugs and medical devices. By getting the grants, the overhead, the licensing fees, and a cut of the profits, these parties are triple dipping into the trough and creating conflicts of financial interest.

- Create a national, non-profit association to develop all drugs and devices created, in part or whole, from public grants. This way, the motivation is in seeing bench-to-bedside interventions help people, putting the patient first, rather than maximizing profits.

Pricing drugs beyond their real costs, at a level that is simply what some believe “the market will bear” is an abuse of the public trust: The public that provided the dollars from which the grants were awarded that made early study and development possible. Such high prices are also a violation of social justice in that they invariably are only available to those of the highest socioeconomic realm. Alternatively, we might rethink our system of health care treatment delivery and decide as a society, that such treatments are valuable and therefore, like ESRD, use public funds to pay for the interventions (though in a sense, that is the government paying other parties twice—for development and then again for treatment). The most radical approach would be to halt bringing such interventions to market until they can be offered at a price that is more affordable.

No matter the direction we choose, the release of gene therapy necessitates a national conversation about this new class of products and their role in our health care system. Such a conversation should be inclusive of scientists, industry, insurers, ethicists, health policy experts, and public members. We should be making well deliberated decisions about how to deal with these mega-dollar drugs to develop well-crafted policies rather than simply reacting to the world that these private companies force upon us.