by Craig Klugman, Ph.D.

Last week, the faculty at my university were sent an email about an “exciting “new way to fund our projects and research—raise the money ourselves. The university has contracted with a crowdfunding company to allow us to have university branded pages to raise money. So far, I have seen student listings to pay for their summer travels, a field trip for students to attend a basketball game in another city, and a request to replenish funds for a student emergency fund. Our administration has suggested we could use this program to raise money for class materials, research projects, or other supplies that we might need to do our work.

What is crowdfunding? This model is where a project will raise small amounts of money from many people. For example, say you want to buy a house. Traditionally you would go to one bank and get a mortgage for say, $200,000, from that bank and then pay them back over 15-30 years. If you crowdfunded, you would ask 10,000 people for $20 each and never pay them back. People have crowdfunded trips, college tuition, medical expenses, funerals, and much more.

Might crowdfunding be the new neoliberal model for funding higher education? The potential pool of college students has declined since the current crop of teenagers is a smaller population than the group that preceded it. In other words, there are simply fewer people to fill the seats in colleges. We have fewer people available to pay tuition. Add that fact to the decreased federal and state support for education, and our institutions of higher education are facing a financial crisis. In fact, my campus is expecting a budget report to drop any day now that cuts spending by finding “efficiencies” and reducing “duplications” in the workforce. I suppose it is no coincidence that our crowdfunding site dropped when it did.

My school is not the only one heading toward crowdfunding. A new report from the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) studied 700 research projects listed on a science crowdfunding website, Experiment.com. This website allows people to contribute money to listed projects in all areas of science. The amounts tend to be modest from $10 to a few thousand. They have over 700 projects on their site and about 45% get their funding. One project allows people to donate money and then spend a week digging for dinosaur bones. Other listed studies allow one to sponsor faculty or students, supplies, or even a rental truck. Some projects ask for contributions toward a larger goal rather than allowing people to sponsor individual parts. Once you have contributed, you can follow the research by looking at a “lab notes” section of the site in an attempt to keep people informed about the work that they help fund. Like most crowdfunding, if the stated financial goal is not reached, then all pledges are canceled and the project gets no funds at all. This is an incentive for the researchers to recruit people to pledge through social media, flyers, and their personal social networks. If you want to get a project funded, you must market it. Proposed projects are reviewed internally by the Experiment.com staff, but no peer review. The website stays in business because they get 8% of the pledges plus an additional 3-5% for payment processing. The researchers only get 87 cents of every dollars pledged. This is actually a higher rate going to the work than most donations to charity.

The NBER study found that the projects most likely to be crowdfunded are those by researchers who have a harder time being funded by grants and foundations: Successful crowdfunding researchers are more likely to be junior scholars and more likely to be female. A person’s prior productivity is not correlated with success in being crowdfunded. Perhaps these populations are more social media savvy and have larger social networks that allow them to recruit and fundraise more effectively.

My university’s crowdfund site has a $10,000 limit, but if we do not make our goal, we get the lesser amount of funds. So if I ask for $10,000 and end up only getting $3,000 in donations, I get the $3,000. However, I now have to do the project on a much smaller budget or do a small piece of the whole project. In our case, since the donation is made to the university’s website, pledged money is tax deductible. Another difference is that while most sites ask you to provide gifts to people who donate (from thank you notes, to t-shirts, to helping out), we are not allowed to offer any incentives.

Supporters of academic crowdfunding say it allows everyone to become involved in research. If someone has an interest in a topic, they might feel good knowing they gave some small funds to help further research in that area. The public can become more engaged with research by getting updates as discovery takes place. These platforms enable researchers to connect with the general public in order to create excitement for their work and bring their findings to a larger population.

Philosopher and bioethicist Jeremey Snyder wrote about the ethics of crowdfunding to raise money for medical treatment in The Hastings Center report: “I argue that medical crowdfunding is a symptom and cause of, rather than a solution to, health system injustices and that policy-makers should work to address the injustices motivating the use of crowdfunding sites for essential medical services.” Use of these websites for medical treatment funding means that a person gives up privacy since the listings require you to put in a lot of information to generate interest, to inform, and to motivate people to donate. Also, these sorts of sites are not necessarily accessible to everyone—successful funding is often correlated to one’s looks, the power of one’s story, how big your social network is, and your online skills.

One of the concerns over industry money in bioethics is that such money creates conflicts of interest that result in bioethics being beholden to outside interests. In 2005, philosopher and bioethicist Carl Elliott expressed alarm at the effect of industry money in bioethics: “As bioethics becomes more strongly entrenched in bureaucracies that are paying for its services, it may well be transformed into a field that looks very different from the way it looked a decade or so age. Bioethicists will start to look less like scholar” Is this risk lessened when there are 200 people contributing $20 each opposed to one large donor? Or do academics become beholden to many more people as we have to recruit further and farther to fund out operations.

Crowdfunding in higher education is “development” and “advancement” (i.e. fundraising) for smaller amounts of money. In part, it does not pay for development officers to seek small amounts of money, so they go after the big dollars leaving more modest needs unfulfilled. While funding research on these sites has been popular so far, there may be many other uses. We have a public health bowl team that might find this approach useful for raising money to attend the national competition. Maybe I want to use an expensive textbook in my class and can create a fund to help subsidize the cost to students. Given the very modest amount of travel money I receive, maybe I can ask people to help support my travel to present at conferences. As universities cut their budgets further we may have to crowdfund for that new computer or even to pay the portion of one’s salary not covered by grants.

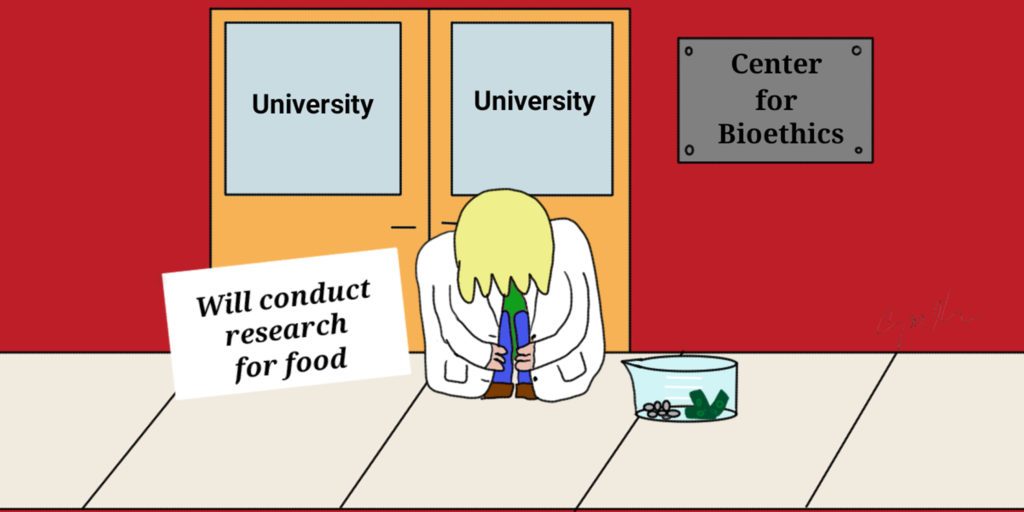

While crowdfunding might seem like an exciting, new way to infuse money into higher education, it gives me great pause. When I learned about our university’s new website, I was appalled. In academia, cans have a way of becoming musts. Will I be required to hit up my friends and neighbors to raise money for new classroom equipment? Will part of my annual evaluation include the amount of crowdfunding money I raised? I understand that this approach is meant to help reduce the deficits created by decreasing state and grant budgets. However, the approach also changes the nature of what we do from scholarship to salesmanship. And if we prove that we can raise our own funds, there may not be an incentive for states and the federal government to invest in higher education.

One might also ask whether this is really a change in how we fund research. After all, most projects required applying to agencies and foundations for money to do scholarship. This new way allows people to fund research without the involvement of the government. It also means no peer review, no oversight, and no accountability. The same can be said for funding more of higher education through crowdsourcing—classroom supplies, supplies, and even salaries—it rewards those who are more social, more active online, and have contacts who can afford to donate. This might be a nice way to fund small projects that we may have paid for out-of-pocket before, but it should not substitute for a robust public system to fund research, teaching, staffing, and infrastructure.