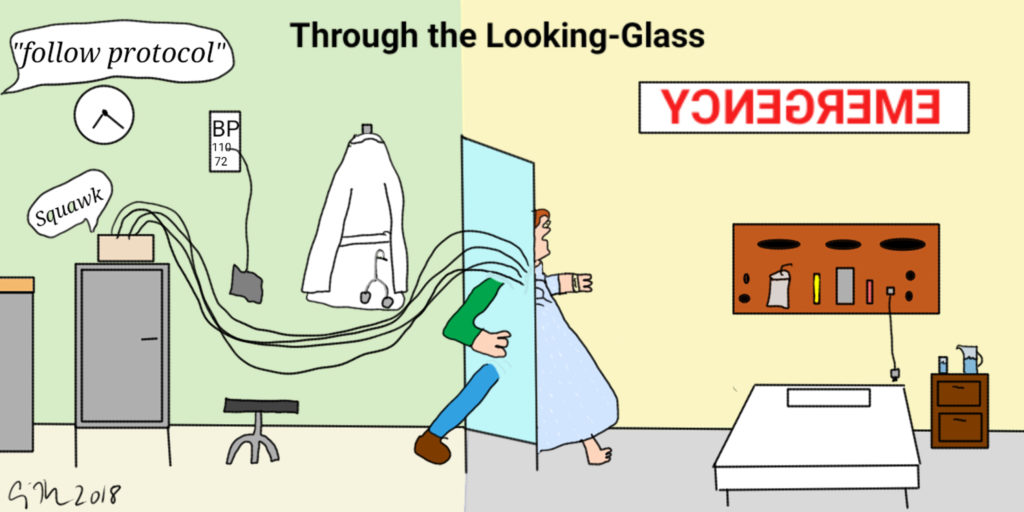

by Craig Klugman

A new JAMAarticle reports on a US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation against routine ECG in patients without symptoms of heart disease: “For asymptomatic adults at low risk of CVD events (individuals with a 10-year CVD event risk less than 10%), it is very unlikelythat the information from resting or exercise ECG (beyond that obtained with conventional CVD risk factors) will result in a change in the patient’s risk category….”The report states that over-screening can lead to harms such as “invasive procedures, overtreatment, and labeling.”Such advice follows with recent suggestions against many preventive screenings that were de rigueur just a few years ago for prostate cancer, breast cancerand more (the one exception is a recent expansion of colon cancer screening). In most cases, the potential harms of protocols that require follow ups to false positive tests outweigh any benefits. Often such recommendations receive pushback from patient organizations and patientswho believe there has to be benefit in the screening (based on single cases) despite the lack of population-level evidence.

The dangers to screening are real and cost us time, money, medical resources, and exposure to risk. I know because it happened to me.

In June 2017, I went for my regular annual physical (okay, bi-annual physical in my case). Since I am now a man of a certain age, that physical included an ECG. The nurse wheeled the machine into the clinic room and proceeded to attach a number of sticky round disks to my chest (i.e. “leads”). She then pressed a button and a series of bright lights flashed. The machine hummed until it made a sharp, loud noise and then stopped. The nurse turned the machine off and then on again. Nothing. She said, “I think we’ll have to get another machine…Let me try something.” She unplugged the machine and plugged it back in. The machine did not exactly restart but she was able to get a printout. The nurse left the room.

About ten minutes later the doctor reappeared. He said, “I don’t want you to worry but there was an odd reading on your test and there are steps we have to take.” He handed me a baby aspirin and one of those tiny, paper cups of water. He then explained that an ambulance was on its way. Apparently the test strip managed to capture eight beats and that seventh, the one where the machine’s odd noise began, registered a blip.

“Could that odd reading have come from the machine malfunction,” I asked. “Maybe we should start with getting another machine and a new reading? I can even walk over to a cardiology office in the building?”

He put his hands on his hips and was adamant, “I hope you understand that I have to act conservatively. It’s for your best interest”

One of the strange things is that his office was in a building attached to the hospital. “I feel fine,” I begged. “Can I just walk over there.” I was assured this was not possible, as this movement could be dangerous. Besides, I had no entered a protocolthat had to be followed.

A few minutes later two EMTs entered the small room. They put me on a tiny wheelchair and took me to the front of the building where I was loaded into the ambulance. The EMT attached me to her ECG machine and said to her partner, “I don’t see anything here.” I told her what the doctor had told me. “Well, everything looks fine here. Did he give you an option to not call an ambulance?”

“No, he just called and told me this had to happen.”

She then explained that they could take me or not, but I would have to sign a waiver in case I collapsed when walking away. Even though I know better, I asked her what would she tell her husband to do. “If it were me, I might risk not going to the hospital. But if it were my husband, I would be angry if he didn’t go.”

I am married to a physician and was thinking he might respond the same way: He would be angry if I did not go. So, off we went. I was strapped into the gurney and the two EMTs got into the cab and we drove, around the block. We went about 1000 feet total to the ED ambulance bay of this private hospital connected to my doctor’s office.

I was immediately placed in a hallway (all of the bays were busy) and connected to long term monitoring. A bevy of nurses and medical aides drew blood, took my temperature, measured my blood pressure, and asked about my medical history. There is no immediate family history of heart problems.

“When did your chest pain begin?” they asked.

“I don’t have any chest pain,” I responded.

“When did you start feeling tightness in your chest and trouble breathing.”

“I don’t have any tightness in my chest or trouble breathing.”

“When did you start feeling pain in your left arm.”

“I don’t have any pain in my left arm.”

I was left alone for several hours. I called a friend who came over to keep me company and against my stated wishes, she called my spouse who was working 2 hours away. A cardiac fellow stopped by and said they would be monitoring me for a while.

After a few hours I needed to pee. I asked the nurses if I could. They disconnected my leads from the monitoring device and pointed down the hall. This was my first real indication that my health care providers did not think I was having a health emergency. I walked down the hall, took care of my needs, and returned.

A few hours later I was told that I would be admitted overnight for observation. This, as it turns out, was a partial truth. I asked if I could be released to go home and promised to come back the next morning for a stress test or whatever they wanted. When my husband showed up, he looked at the medical chart and reaffirmed that everything looked fine—I had no indications of a heart attack and 5 hours of telemetry showed a continuous and normal rhythm.

Then I was moved to a cardiac floor via wheelchair. The nurses set me up in the bed, but again, seemed to be treating me as a person who was not ill and not at risk. They inquired about what I wanted for dinner. When I asked if there were any dietary restrictions, they told me “no.”

At this point my husband turned to me and said, “You know that I feel strongly that patients should listen to their doctor but in this case, I would not be against you leaving AMA [against medical advice].” The nurses agreed that it was a bit silly that I was being kept overnight. They even joked with us about how healthy I was. They explained that the cardiologists all go home by 3pm and since it was well after that, I would have to wait until the morning when the specialists arrived and could decide what to do with me. So, my physician-spouse called the cardiology service and demanded to see the cardiologist on call (insider privilege). We were told that he was on the other side of the hospital and could not get there.

An hour later the fellow called and said that he had looked at the record and saw no reason to keep me there or to have me follow up. We were released. I walked out of the hospital on my own (no escort, no wheelchair). Seven hours after arrival, I was able to go home.

The next day I contacted my primary care physician to follow up. I told him what had happened and asked him if he wanted me to follow up with a cardiologist, schedule a stress test, or anything else. He told me “No, you were evaluated and we do not need to do anything else. I hope you understand that I had to do this.”

Four months later, I received the billing statement. The cost of the ambulance ride was $1,000 and was covered by insurance. Insurance also paid $7,000 for my cost of care for 7 hours and I had a $1,000 copay. This unnecessary testing that necessitated following a scripted protocol cost $9,000. So, yes, I know the risks and costs of over-screening to myself and to the health care system. My care was dictated by a protocol and a reaction to an anomalous reading (that was in all likelihood a machine glitch). Despite the fact that I had no symptoms, that one blip (and likely a huge fear of liability) led to an expensive, time consuming, anxiety-generating, and resource intensive waste of time. Yes, I know that my treatment demonstrates my privilege as someone with good health insurance and that if my skin was darker, my elocution was coarser, or my insurance was nonexistent I probably would not have had this experience. I also know that once this protocol began, stopping it required a titanic effort which was also a form of privilege—someone who is a clinical ethicist and is married to a physician. Privilege, blind adherence to protocol, and over-screening got me into this mess and only privilege got me out.

I have not gone for an annual screening this year (the literature is lending doubtto the value of this ritual) but I am considering finding a new PCP, one with critical thinking skills and not so much dedication to single-mindedly following a decision tree.