by Craig Klugman, Ph.D.

“Whoever kills a person [unjustly]…it is as though he has killed all mankind. And whoever saves a life, it is as though he had saved all mankind.” (Qur’an, 5:32)

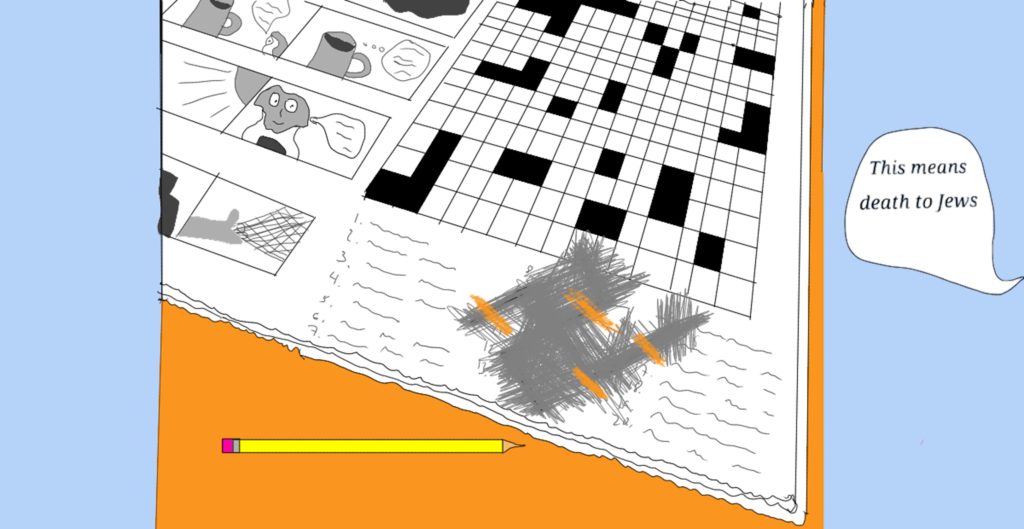

When I was about 7 years old, my father was completing the newspaper crossword when he called me over to sit in his lap. There had been an incident at the Temple and it was time for me to have the talk that every Jewish child has at one time or another. We lived in a small, conservative, blue collar town that was predominantly Catholic. It was a place where the schools scheduled important tests on the Jewish Holidays and make it difficult for us to make up the work. On that summer morning, my dad drew a swastika in the corner of the paper. He told me, “This symbol means death to Jews.” At the time, I did not understand that he meant that this was a symbol adopted by people who hated Jews; I thought that the symbol itself could cause death. I grabbed his pencil and immediately crossed it out over and over until the newsprint shredded.

Last week, my spouse and I had an argument about our mezuzah, a container for the traditional prayer scroll that all Jews are supposed to mount on the doorposts of their house. Ours fell down because the glue I used (metal doorplate) didn’t quite make it past a year-and-a-half of Chicago weather. He said that we should not put it back up; we should not draw attention to ourselves. I have argued the opposite, that it’s our duty to display it not only from a religious stance but from a stance of being proud of who we were. After this weekend, that mezuzah is still sitting on a shelf.

According to the Anti-Defamation League, the number of hate, anti-Semitic, and terrorist attacks in the United States is at a high level and increasing. By tracking these incidents on an explorable map, it is possible to see what acts have been committed, by whom, and their ideology. In the years 2017-2018, 3,023 acts of hate were committed in the U.S. Of those, 4 were committed by people with “left wing” beliefs; 8 from people with “Islamist” beliefs, 10 from people with generic “right wing” beliefs, and 1,042 from people with white supremacist views. Apparently, the most dangerous people in America are angry, white male supremacists who believe they are better than all other people.

The killing of 11 people in a Pittsburgh synagogue over the weekend is the latest manifestation of growing acts of anti-Semitism in the U.S. and it capped off a week filled with white, conservative, Christian, straight, cis-gendered, men killing and attempting to kill people who are different. From the synagogue terrorist attack, to mailing pipe bombs to Democratic leaders, to shooting black shoppers at a Kroger, and the further election of right-wing leaders across the world, we are facing a rise in people acting on hatred to harm others.

What then, is a bioethics response to hatred? There is not much room in the philosophical and theological theories upon which bioethics relies for hate. Kant and other deontologists would not find a moral law that would allow for hating and diminishing some people but not others. Utilitarian and consequentialist positions would run up against the Harm Principle in trying to justify othering—“treating people from another group as essentially different from and generally inferior to the group you belong to. Virtue ethics would find no place for hate in the character of a good person, and certainly not acting upon it. Feminist ethics soundly rejects it and mainstream religion rejects hate as well.

A bioethics lens would ask why there is so much focus on the Pittsburgh synagogue terrorist attack? In one sense, this is the largest mass killing of Jewish people ever on U.S. soil. But consider the minimal media coverage of two people shot in a Kroger this weekend. Or that this weekend alone 5 people were shot to death in Chicago and a further 38 were injured by guns. Why have these stories received so much less airtime? Racism. Most of those victims were not white. In the U.S., Jews are sometimes viewed as white (and sometimes we are not).Our national narrative is that white people (and Jewish people) do not get shot. The Chicago and Kroger shootings, however, represent that we have, sadly, come to expect black and brown people to be victims of shootings (from each other, from police).

From the 1790s, Jews were labeled under the Naturalization Act as “free white people”. In the 19thand 20thcenturies, however, Jewish immigration was restricted. “Those Jews” had their own language (Yiddish) and their own holidays. Anti-Semitic policies limited the ability of Jewish people to join some professions, clubs, universities, and neighborhoods. Jews are “white” when they are viewed as having assimilated, having shed those affectations that made them “other” and adopted “white” habits and ways of life. Even in supposedly inclusive environments, Jews can be othered: In a spring Chicago March for lesbian rights, a Jewish group was rejected from participation. It is a scenario where others determine our “race” and whether we are included or not, on a case-by-case basis. Jews are white when they are like Christian, Northern Europeans. Thus, most of the time, most of us can “pass”. A Pew research report from 2013 found that 94% of U.S. Jews consider themselves to be “white” (I wonder if that would be different today). However, we are not white when we practice our religion, speak a different language, dress differently, or somehow act outside of the European mainstream. We are not white when we are viewed as a threat by those who espouse blood libels and conspiracy theories that go back thousands of years. I never saw myself as “white” because I grew up in a town where we were considered to be “other”. For many Jews, we think about an escape plan because history has shown us that at some point countries turn against us in attempt to blame someone else for problems.

Why is there so much more hate now than a few years ago? I don’t think there is. I think it has become more acceptable to act upon hate now. I’m not naïve enough to think that people do not have racist, misogynist, anti-Semitic, anti-LGBQT, anti-disability, ageist, xenophobic thoughts. But it seemed that a few years ago, people with such thoughts did not act upon them. Now in this new climate of “nationalism” and “white supremacy” in the White House and in other halls of power throughout the world, people are acting on their hate, and that is a step too far. A bioethics response to hate and terrorism is to provide a rational and logical analysis of the facts, viewed through the lenses of philosophical theories. That thought process leads to only one conclusion, there is no room in the bioethics pantheon for theories or positions that support positions of hate or acting so as to harm others. As bioethicists, it is our duty to speak out against hatred and injustice wherever we see it. It is our duty to point out when lies are being sold as truths to bend people toward hate and division. It is our duty to educate and promote critical thinking. These are also our same duties as human beings on this planet.