by Craig Klugman, Ph.D.

A ProPublica investigation discovered a pattern in some transplant patients at Newark Beth Israel Hospital (NJ): In a few cases, patients were kept in the ICU for one year after transplant and then quickly sent to a long-term care facility where they died. The story came to light when ProPublica learned of Darryl Young, a heart transplant patient who suffered brain damage during his surgery and remains in an unresponsive state (PVS). The reporters apparently brought the story to the patient’s sister who had no idea that her brother was only being kept breathing to help the hospital’s statistics.

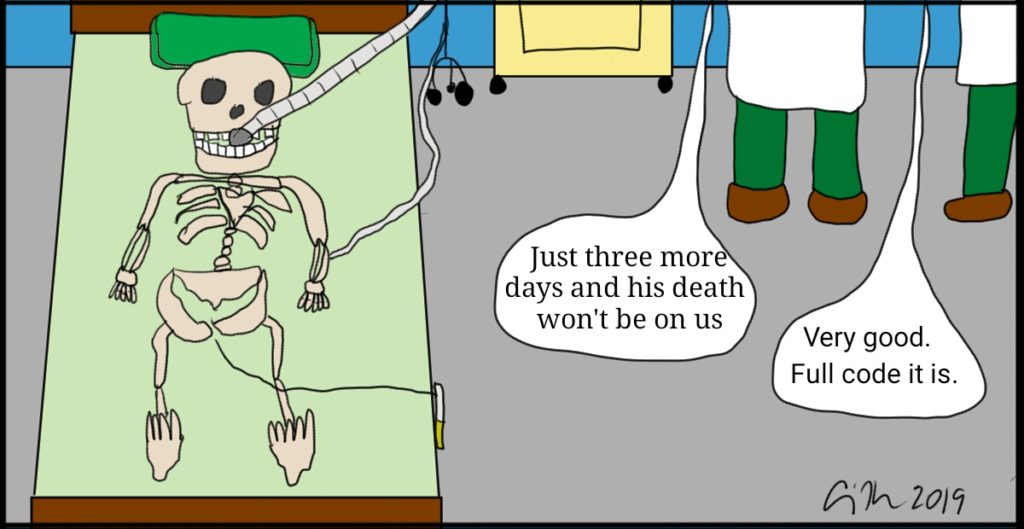

Transplant centers are rated on their success rates. CMS requires programs to report their one-year survival rate. A program that has too many deaths will not only be ranked lower (and could be closed), but will lose federal dollars. If Young could be maintained for the one-year mark, then his death would not be attributed to the transplant surgery and would not negatively effect their funding and reputation.

The family was not informed that Young was in a vegetative state, nor were they told about the option of a DNR order or palliative care. The family, according to the report, never asked because they trusted that their doctors were doing what was best. Young was maintained on body supporting technologies for the hospital’s benefit, not for his own.

In the majority of medical cases, patients have a right to autonomy, to make their own medical decisions. This right has been supported not only in philosophy but also in legislation and in case law. If the patient is unconscious, has altered mental status, or is otherwise unable to make their own choices, then a health care surrogate can make those decisions for them. Ideally, this designation is made by the patient (before it is needed) by appointing a medical power of attorney (MPOA). For Young, his sister was his proxy–she visited him frequently and had the legal (and ethical) right to make decisions for him.

To make decisions as a patient or as a proxy decision-maker, however, a person needs to know the diagnosis, prognosis, treatment plan, risks, benefits, and alternatives. In this case, the sister did not know because she was not provided with the full information. The hospital seemed to be taking a position of lying by omission—if the family does not ask, we will not tell. Under medical ethics obligations, it is incumbent on the health care provider to give information to the decision-makers. Since family and patients are usually not health care providers, they cannot be presumed to even know what information for which to ask. Thus, as part of the fiduciary relationship, the medical team must provide that information. There is no doubt that autonomy was violated in this case.

ProPublica brought their findings to Art Caplan whom they quote saying, “Prolonging ‘dying’ to preserve a flawed transplant program makes a mockery of transplant medicine and is an assault on both ethics and compassion.” Even the director of the transplant program said in a recorded internal meeting, “This is a very, very unethical, immoral but unfortunately very practical solution, because the reality here is that you haven’t saved anybody if your program gets shut down.” The director statement is a dismissal of a deontological standpoint (patients have autonomy) and embraces a utilitarian one (does not matter if someone is hurt because the greater good is served by the transplant program continuing). But this is flawed utilitarian reasoning because a poor-performing program does not benefit the majority, it only benefits the hospital (reputation and finances).

There are a few cases where physicians often act unilaterally without patient or MPOA input. Many hospitals have a presumptive DNR suspension when it comes to surgery and recovery. Oftentimes these are unwritten, hidden, policies. Some surgeons will not operate on a patient with a DNR in place. The reasoning is that there may be an adverse event during surgery that can arrest the patient’s heart. This arrest is caused by the medical procedure and may be reversible. In this line of thinking, since the problem is caused by the surgery or anesthesia and not the underlying disease, efforts should be made to reverse the damage and the DNR does not apply. Another reason for such suspensions is similar to the Newark Beth Israel case, a patient dying on the table can negatively effect a doctor’s stats. Such policies, however, violate statements by various professional associations: American Society of Anesthesiologists, American College of Surgeons, American Association of Nurse Anesthetists, and the Association of Perioperative Registered Nurses. Instead, these organizations suggest “required reconsideration” where the care team and the patient/family/MPOA discuss the situation and come to an agreeable decision. If no decision can be reached, then an ethics consult should be requested.

There are other situations where hospitals act for their own interest rather than for the patient. Consider quarantine for infectious patients to prevent the spread of disease. However, even in this case, the isolation benefits other patients, not the infected patient or the institution. Other medical centers may have a practice of “upcoding,” that is of assigning patients a primary diagnosis that will lead to a higher reimbursement. However, such an action is not only unethical (it is a form of lying) but it is also illegal (insurance fraud).

Of course, collecting statistics in the way that CMS does encourages hospitals to game the system. A transplant program worried about its statistics might reject patients that they view as risky or as too sick to have an assured positive outcome. They may view the risk-benefit analysis differently and reject patients who might benefit but aren’t guaranteed to benefit.

There is one other potential explanation for this case: Racism. The patient and family were Black. Would the hospital and doctors have done this to a Caucasian family?

There is no way to justify the actions of this health care team and institution. In regards to patient and family rights, these health care providers ignored their fiduciary duty and violated autonomy. This patient and their family were used as a means to the end of keeping their jobs and their gravy train. In ethical medicine, the patient must always come first. Here, the patient wasn’t even a consideration.