by Craig Klugman, Ph.D.

A study published in the May 17th, 2018 issue of Cell, “Disease Heritability Inferred from Familial Relationships Reported in Medical Records,” shows a connection between families and certain diseases at three large urban university medical centers. The researchers took private health information from electronic medical records, identified family trees by matching emergency contacts, examined diagnoses and other health information, and matched that with any tissue samples from biobanks to build a picture of disease heritability. The people whose private health information was used have no idea that the study occurred.

This study is similar to the recent revelation of Facebook data being used and shared without permission if a friend consented to a quiz. I did not consent, but my data was swept up because a friend clicked a button. This study feels very similar to that. Private data and records were used in this study without informing people, without asking if they would like to be part of the study, and without giving them a chance to opt out. On Facebook, there is no expectation of privacy: It is clear that we pay for this free service by giving away our information which is repackaged and sold. In medicine, there is a strong expectation of privacy going all the way to the Hippocratic Oath. The risks are real: Matching records like this could bring to light some family secrets that people would rather not be known. What if dad has a second family that the first knows nothing about? What if the mother has a child from her past that her current family does not know about?

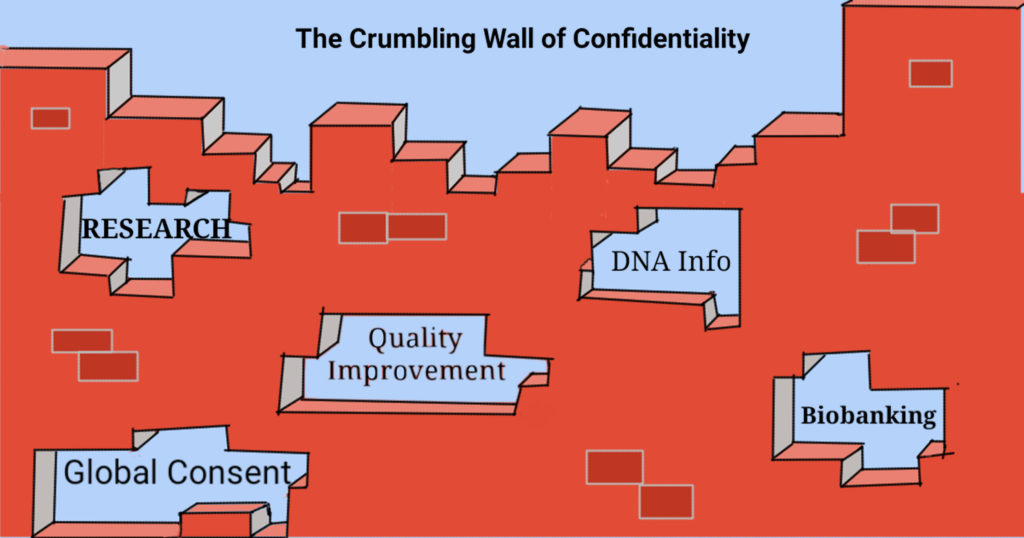

In IRB reviews, the most scrutiny is usually placed on collecting data from subjects whether biological samples or words. This study used “retrospective records” meaning the data already existed. Since the data existed already, any “harm” would be viewed as in the past and the level of review is much lighter (exempt or expedited). This study shows that our working assumptions are wrong—with the ability to connect my record with other people’s and then with biological samples stored in another place, rules that were built for assessing privacy risks of a single database or a single record are no longer sufficient to protect confidentiality.

In most research studies, potential subjects are told the risks, benefits, and alternatives. They are given a chance to consent or not to consent, and can withdraw at any time. But in a records review they do not learn anything about the project, they do not consent, they do not get to withhold consent. They cannot opt out because subjects are not even aware that their data is being used. However, this information was not collected as part of research but as part of the medical care of patients. Patients have an expectation that their medical information will be used for their benefit, not for a research project that puts their privacy at risk. Signing a consent for treatment should not include giving a right to my entire medical file and biology for any use, forever.

A few months ago, I saw my doctor at a large university medical center where they had recently adopted a new electronic health record. I had to electronically sign a new global consent form. With paper forms, I could scratch out the parts with which I did not agree. But the new form did not offer that option. These new forms required me to be on a contact list for fundraising, required me to give permission to the institution to use any and all of my information and biological materials for research purposes and that they would own it. They would not have to reveal to me what they would do with my data or samples, how it might endanger or benefit me, nor would I be able to opt out of it. If I refused to sign; if I refused to give them permission to put my information in the EHR, then I would not be permitted to see my doctor. I do not have a choice to opt out of an EHR, meaning that these patients were drafted into being part of a research project without their knowledge or permission. These generalized, universal consent forms are a violation of patient autonomy and trust we hold in health care providers. Consent for treatment and for research should remain separate.

In the paper, the authors recognize that there are some ethical concerns: “How best to balance the competing demands of protecting patients’ privacy with clinicians’ duty to warn relatives of potential genetic risks.” The authors recognize there data sweep could be viewed as a HIPAA violation: “In the United States, accessing a family member’s health information in this manner may be considered a violation of the 1996 Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Privacy Rule” However, the authors hold that case law may establish a duty to inform about familial genetic risks. While there is agreement and long established precedence for HIPAA, the notion of a genetic duty to warn is not well defined. Such a proposition assumes that genetics dictate your life: A genetic predisposition is a tendency but not a guarantee of what a person will experience. A person’s genes are moderated by environment, diet, exercise, and exposures.

The irony in this case, is that researchers are not sharing any of their findings with patients. The very ethical reason they cite to justify this project is the one thing they do not do—the researchers undermine their own argument. In a physician-patient relationship, there is a fiduciary obligation whereby a patient shares secret and private information to get help needed now. In research, a subject shares information, scans, and biological samples in the hope of a future benefit for others. But if data given under an expectation for near-term clinical help is now being used for providing a fuzzy future benefit to others, and the reason for violating confidentiality is a genetic duty to warn, then it seems that the fiduciary duty should transfer to the researchers and they should be giving notifications to the unwitting subjects. Their reasoning is that they are acting as clinician (duty to warn) and not as researchers (no duty).

The study says, “The EHR data used in this research are nearly ubiquitous and, if privacy is adequately protected, could allow almost any research hospital to identify related patients with high specificity.” My question is whether privacy can be adequately protected. Other studies have shown that it is fairly easy to re-identify deidentified information, especially when it comes to genetic information. Beyond the process of finding genetic diseases within a family, might hospitals use this for marketing purposes—I receive a message saying that because my cousin has a disease, I should get checked—selling me more services HIPAA does not permit the selling of medical data to outside sources, but it may allow the hospital to try to sell me a service from data it got from its own records. There are social implications as well. Could a family be stigmatized because there is a chart showing a family relation has a certain potentially-genetic disease? Might these files prevent me from getting life insurance or being hired on a job because the cost of health insurance would be too high for an employer. Historically, the idea that hospitals are building family trees for each of us echoes back to eugenics policies which led to the sterilization of hundreds of thousands of Americans because their family was judged as having undesirable traits.

Beyond their brief statements about violating HIPAA, there is further indication that researchers were concerned about loss of privacy. The researchers did not mix data between hospitals. It is not uncommon for people in the same family to visit different doctors in different systems. This move suggests two things: One is about ownership of the data—perhaps there is potential to monetize this information, similar to social media so hospitals do not want to share records that they own. And second, not sharing data was a recognition that there was a step too far in violating their patients’ records.

Clearly, we are going to see more and more of these big data studies and more and more of these cases of institutions viewing all data shared with them as their property to do with as they please. There needs to be better ethical oversight and regulations to address this turn in order to better protect privacy and patient/subject autonomy. We must also remember that patients are not subjects until they are consented. Ideally, researchers would contact all potential subjects (i.e. everyone with a medical record) to get consent but that is impractical. Instead, I suggest that researchers be required to put notices on patient portals, in doctors’ offices, and even in local news media that the research is occurring, providing a contact if people wish to learn more, and providing a method for people to easily opt out. Otherwise, we are telling patients to be like social media users—share at your own risk. The result may be that patients hold back information, not knowing how it will be used.

For myself, the next time I am asked for an emergency contact I’ll refuse and if that doesn’t work, I’ll give fake information. Some may argue that it is unethical for me to lie and that it will prevent my physician from offering help. I respond that with this move, hospitals have said they are not interested in trust.