by Craig Klugman, Ph.D.

Last December, I wrote a post about #MeToo in bioethics. I wish this could be a one-time topic and all of the problems were fixed, but alas this is a problem of structural inequality. Thus, it is a topic that we all need to revisit on a regular basis to ensure that we make real changes.

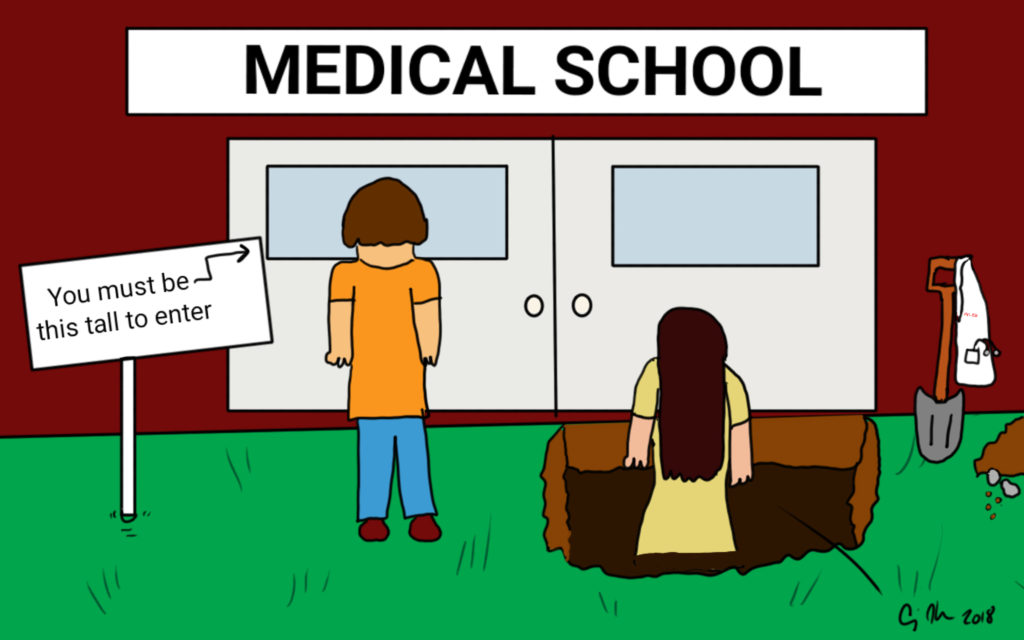

The latest reminder of gender and sex inequality comes out of Tokyo Medical University (TMU) which reported a much higher admission success rate for men (8.8%) over women (2.9%). The result is a significantly higher proportion of men entering medical school. Admission to TMU is based in large part on an entrance exam. TMU officials have admitted that since 2006, they have “routinely lowered the scores of all female applicants” in order to keep a higher proportion of men in medicine. After all, the officials, said women have shorter careers in medicine because they leave the profession to have children. They provided no data to support this claim.

Might similar problems exist in other countries? In Pakistan, while most medical students are female, they make up less than a quarter of practicing physicians. One proposal there would create quotas for each gender to ensure that more medical graduates stay in medicine, rather than, as a BBC article reports, use their medical degree to find a goodhusband.

In the United States, 48.8% of medical school applicants are female while 50.7%of medical students are female. The 2017-2018 academic year saw more women enrolling in medical school than men. These figures match those of other countries such as Pakistan, UK, and Germany. Of the 147 medical schools reporting the sex of applicants and matriculants to the AAMC, only 47 (32%) had 50% or more of their applicants identifying as female. Of those 47 with more female applicants, 26 (55%) had a class where the number of female students was the same or more than the number of men. Having more female applicants, as TMU shows, does not always translate into having more female students.

However, of the 100 institutions that have more male than female applicants, 45 matriculated more female than male students. In total, that means 48.3% of all AAMC medical schools matriculated more women than men. That still means that over half of medical schools have a male majority class. How can that be when there are more women in medical school than men? The answer is that the schools admitting more women likely have larger student body populations. For example, if med school A has 200 students in a class and 55% are female (110 students) and med schools B and C each have 30 students but only 45% are female (27 students total) then nationally there are more female than male medical students (137 female; 123 male) even if fewer schools have more female than male students. It comes down to how one does the math.

Of course matriculation does not tell us about offers. Most students apply to more than one medical school but can only attend one. Do women or men receive more admission offers? Certain schools may attract more female candidates to apply and others may not be as popular a choice for admitted female students. This leads to the question of graduation—do more female students mean more female medical school graduates? The Kaiser Family Foundation reportedin 2017 that 47.4% of medical school graduates were female. In only 9 states did female medical school graduates outnumber their male peers. In 2 states, women made up less than 35% of graduates and in 19 states they made up fewer than 45%.

Then there is the question of whether women have a similar experience in medicine than men. After all, TMU cited their reason for manipulating scores as being that women leave the career earlier (even though they provided no data to back up this claim). The data is not encouraging—women have a harder time than men in medicine and face more discrimination. They have double the burnout, seven times the patient harassment, a widening pay gap, minimal representation as chairs and deans (15%/16%), and a higher suicide rate (2.5-4 times the population).

Women in medicine must do the same grueling training and work hours as their male peers. In addition, women still have the large bulk of household and child care duties which leads to more work-home conflicts for time, energy, and attention. The result is higher depression levels in female doctors. Women only make up one-third of the medical faculty. Female doctors are often introduced by their first names instead of as Dr. XX. They havelower rates in leadership rolesand have a more difficult time rising throughthe ranks. Women compose a lower percentages of practitionersin the most lucrative medical specialties (anesthesiology, surgery, internal medicine subspecialties, neurosurgery, nuclear, radiation oncology, urology). Consider that only 14.8% of orthopedic residentsare female. Even though most pediatricians are female, they earn 79% of what a male pediatrician does.

One other factor is worth considering—the structural inequality in a reporting system that limits sex to male or female. The reports do not offer a definition of male/female. Most often, that identification is based on self-report of the candidate checking a box on a form. But a binary box does not represent the full spectrum of sex in the world. Estimates hold that nearly 1 in 250 adults is transgender, about 1.4 million people(0.6% of total population) in the U.S. This estimate does not include people who identify as nonbinary, a number that has not yet been calculated. Perhaps it would be helpful to know the percent of transgender and nonbinary applicants to medical school to help ensure appropriate representation.

While discrimination against women in medicine may not be as blatant in the United States as at TMU, it still exists. In a sense, asking someone to declare as male or female, with no other options, is a form of discrimination against people who are and who identify as something other than this binary choice. Discrimination by sex or gender violates key bioethics principles—the notions of equity and fairness. Bioethics and medicine have a long way to go in this regard and routing out the everyday, structural discrimination is a much harder task than that TMU initially faces: Ensuring that officials do not manipulate test scores is much easier to accomplish than the subtle structural and institutional discrimination that exists but is not so evident and is so deeply rooted that it is not easily cut out.