by Craig Klugman, Ph.D.

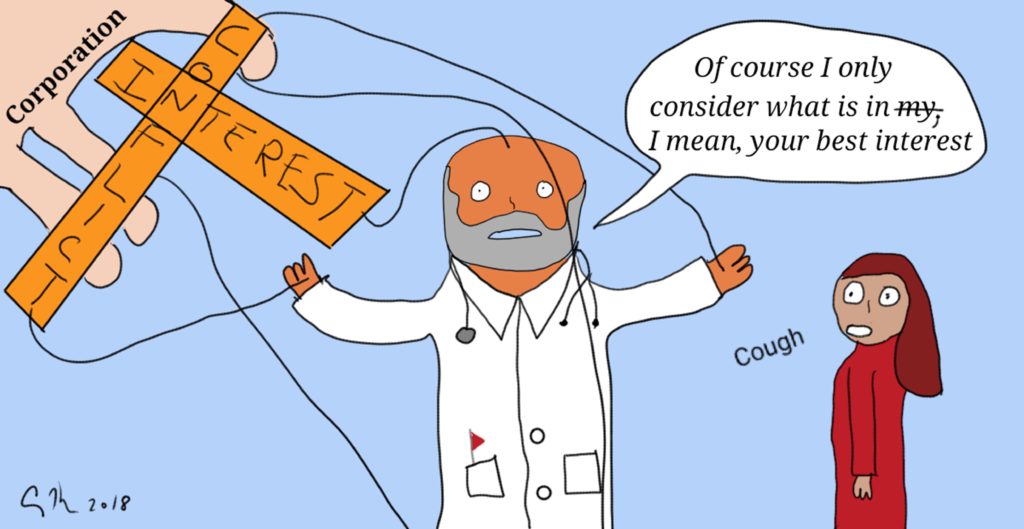

Federal kickback rules state that a pharmaceutical manufacturer or medical device producer cannot pay providers or patients to recommend or prescribe their products. The Anti-Kickback Statute [42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7b(b)], “is a criminal law that prohibits the knowing and willful payment of “remuneration” to induce or reward patient referrals or the generation of business involving any item or service payable by the Federal health care programs(e.g., drugs, supplies, or health care services for Medicare or Medicaid patients)”. This law is one of a group that is intended to protect federal health payment programs from fraud and from conflicts of interest (for example, a physician is not permitted to refer patients to other businesses that they own [42 U.S.C. § 1395nn]). The concern is that money or gifts could influence physicians and patients to use or recommend a drug, service, or facility because of this existing relationship (and self-benefit) rather than because the drug/service/facility is the best option for the patient. In other words, these regulations exist to prevent conflicts of interest.

In a surprising move, the Trump Administration has recommended relaxing these rules. The result would be that companies could pay doctors and hospitals to use their products. Physicians could refer patients to use labs and facilities that the physician owns. The action would reverse decades worth of efforts to remove this undue influence from the practice of healthcare: Think of such efforts as the elimination of free meals by pharmaceutical companies on academic medical campuses and restrictions on medical device companies giving gifts (like free stethoscopes) to medical students. Those changes were made because studies showed a gift with a value as low as $10 can influence current and future prescribing patterns.

As a bioethicist, the idea of removing guidances to prevent fraud and reduce conflicts of interest is abhorrent. These rules, after all, protect patient autonomy by ensuring that physicians offer options that are best for the patient (beneficence) and are not simply best for lining pockets or increasing their professional prestige. Ideally, of course, all physicians would be people of strong virtuous character who would never steer business in their direction or use the potential of personal gain as a way to direct patients toward certain choices. Here in the real world though, people (including patients, physicians and other health care providers) are influenced by external forces. Patients make choices that are preferred by their families even if it’s not the choice they want to make for themselves. If a physician may make extra money by referring patients to a rehab facility the care provider owns, they may provide a discount to the patient to incentive them in that direction. Proof that people do take advantage is shown in the existence of a permanent Medicare Fraud Strike Force (see their action reports here).

So why delete these regulations? Part of this proposed action is because the Trump administration has set the cutting of business-unfriendlyregulations as a key goal. Other reasons cited to support this include efforts by pharma executives and lobbyists to show that the rules prevent insurers from giving rewards to incentivize patients in healthy behaviors (e.g. losing weight) and giving bonuses to physicians who achieve company goals (e.g. reducing costs). The rules also prevent companies from providing assistance to patients on Medicare and Medicaid who cannot afford the cost of their drugs; such programs do exist for people on employer-based plans or who lack health insurance.

My own experience with these regulations confirms that they are imperfect. I was consulting with a company that was offering a medical solution that relied on the patient having an iPhone. As part of a small team of bioethics advisors, we suggested that the requirement of having an iPhone (not any other kind of smartphone or even just a phone) might be discriminatory for people who do not have such a device either by choice or because of finances or technological prowess. The requirement would simply maintain or even increase social injustice. The company took this comment seriously and met with their attorneys, the FDA, mobile providers, and even cell phone manufacturers to find a way to get iPhones in the hands of people who could benefit: A gift? A loan? Part of the prescription? A donation? Anywhere they turned the answer was the same, the anti-kickback statute made it impossible to make this work. The company even proposed buying old iPhones and bricking them so all they could do was use one app and call 9-1-1. Certainly, that would not create an incentive to anyone to use this particular medical treatment just to get a free iPhone. The answer was still no. Thus, despite months of efforts, the result was that this medical device which might benefit some patients would be unavailable to those who did not have their own iPhone. In this case, the regulations reinforced a social injustice (socioeconomic injustice and sociotechnological injustice).

However, the proposed Administration changes are more like “throwing out the baby with the bathwater” than simply finding a better way to wash the baby. These anti-kickback regulations serve an important purpose: To promote patient trust that the physician is not making a choice to benefit their own pocket but instead is acting out of altruism to benefit the patient. The regulations do need some tweaking for cases where the patient may benefit (and not merely to save money—i.e. increase profits—for the company). While most doctors will act responsibly, professionally, and ethically, these regulations are needed to help guide those without this natural inclination toward moral action. Relaxing the rules too far will only create more opportunities to harm to patients; the one thing that must always be avoided.