by Craig Klugman, Ph.D.

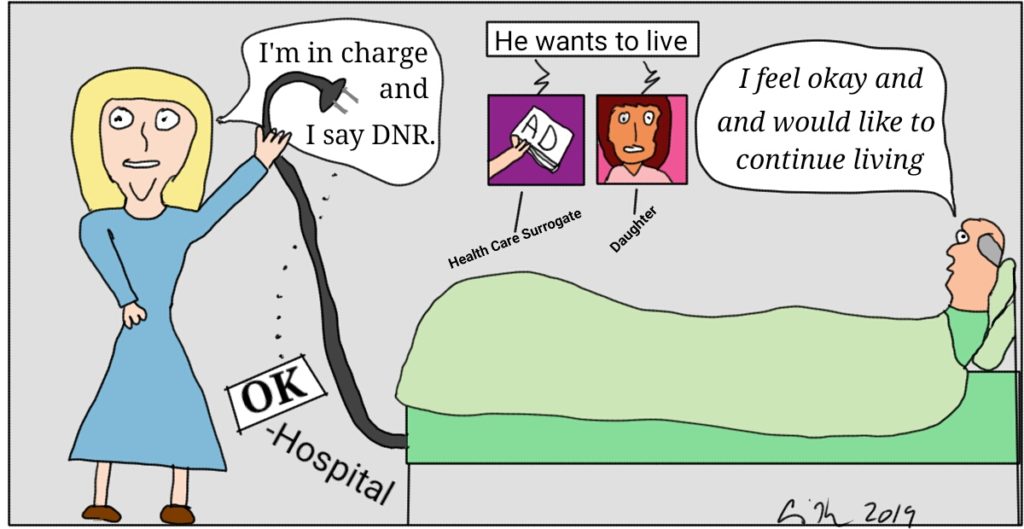

Steven Stryker was 75 years old when he died on May 13 at St. Joseph’s Hospital in Tampa. His death was not avoided when health care providers did not perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Stryker had a DNR order even though he, his daughter, and his health care surrogate did not want it. Stryker had some capacity and some deficits, and a court-appointed a professional guardian to control his affairs. That guardian allegedly has a policy of always putting DNR orders on her wards, and thus, Stryker died. The patient, his daughter, his health care power of attorney, and his psychiatrist were all against the DNR.

When looking at whether a patient can make their own decision, there are two factors to consider. The first is competency—is the patient legally competent to make their own decisions. In this case, a court appointed guardian would seem to suggest no, the patient lacks competency. The second part, however, is capacity. Can the patient mentally, psychologically, and emotionally make a specific decision at a particular point in time. In other words, are there some decisions the patient can make but not others? Could the patient choose what they wanted to eat for lunch but not give consent for major surgery? A patient may have capacity during some times or parts of the day but not others. Are there decisions that a patient lacking competency but having some capacity could make? In most states, a DNR order or advance care document can be withdrawn by the patient irrespective of the patient’s mental status. Thus, a decision not to have an unwanted DNR would fall into this category of choices a patient could make.

According to Stryker’s health care surrogate and friend, he was able to make his own choices. Why then did the hospital override everyone but the guardian? The guardian was Rebecca Fierle, Professional Elderly Care who has been doing this work for 21 years. When Stryker was hospitalized last August for his swallowing disorder while his surrogate was out of town (and the daughter lives far away), Fierle petitioned the courts to be appointed as guardian. We know that the guardian moved the patient frequently between facilities and the family believed this was not in his best interest. Once the guardian was appointed she cut off contact between the patient and his family/friends. With a caseload of 98 charges, could the court-appointed guardian have spent time with this family to understand their wishes and desires? Were there any financial conflicts of interest with this guardian and the many facilities? Why did she move the patient so often? The answers could very well be reasonable and in the patient’s interest, but the answers might also suggest something darker and decisions made to benefit the guardian, not her wards.

This situation may not be Fierle’s first dissatisfied family. Her professional Facebook pagelists her as being located in Orlando, 84 miles from Stryker’s hospital. The comments on her Facebook page provide a less than flattering image. A 2018 case was filed against her in her capacity as a guardian. In 2009, the National Association to Stop Guardian Abuselists a case of judicial misconduct against a judge who absolved Fierle of all wrong doing in a previous guardianship complaint against her. Complaints go back to 2002 in a case where Fierle met with a nursing home resident and had herself named as the resident’s power of attorney. According to court records, Fierle completed a will for the resident leaving all of the money to the facility and naming Fierle as “personal representative”. Fierle’s website is now down for maintenance.

A Do Not Resuscitate Order is a physician-written order. It cannot be demanded by a patient or surrogate (it can be requested). No one can force a hospital into writing one (except under court order). What doctor wrote this order against a patient and his family? There are a lot of problems in this case, but at the end of the day, a physician wrote this order and an attending (and consultants) kept the order in place. These physicians violated the patient’s autonomy and right to make their own choices. An administrator, a professional guardian, and a hospital system cannot write a DNR order. In this case, the buck should have stopped with the attending, but it did not.

St. Joseph’s Hospital is owned by BayCare which owns many medical facilities throughout Florida. The company has a brochure of Patient Rights and Responsibilities. Among the many statements in this document is this one, “At any time, the patient, health care surrogate or proxy can withdraw the DNR order and/or the DNRO form.” There is nothing in here about the patient having to be competent and capacitated at all times to be able to withdraw a DNR. There is nothing here that saying a patient with a guardian will not be heard. Thus, it appears the hospital may have violated its own policy.

The Orlando Sentinel article quotes Fierle as saying she had attended an ethics consultation at the hospital. No details are given but after the meeting Fierle kept her request for the DNR order and the hospital honored it. I wanted to know who might have been at this meeting, what was discussed, and what recommendation the consultation made. Of course, all of this information could be unavailable under HIPAA. To learn more, I called the hospital to speak with someone about the ethics consult conducted. My first call led me down the path of being transferred from office to office. My second and third calls ended in the voice mail of someone who had recently retired (end of April, two weeks before the patient died) and was told that no one would be checking the messages. In total, I made 10 phone calls to both the hospital and the system and never reached anyone involved with ethics. Consider that an ethics consult should be an easy service for both staff, patients, and families to access.

Another big question is whether the decisions of the court-appointed guardian overrides that of an appointed health care surrogate (in this case we have the surrogate’s statement that she was appointed by the patient but no mention is made of whether she has supporting documents)? The answer varies from state to state. In general though, the decisions of the patient-appointed health care proxy seem to have precedence in making medical decisions.

This is a story of misunderstanding and miscommunication. Fierle has now been removed as guardian from all of her charges. This story also leaves a lot of unanswered questions about family dynamics, the process of ethics consultation, the problems with guardianship, and medical decisions followed without consensus. In the end though, why didn’t the hospital listen to the patient?