by Stephen P. Wood, MS, ACNP-BC

I haven’t had this question from a patient yet, but I know it’s coming. The information disseminated by us, to us and for us is a bit conflicting when it comes to COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel virus SARS-CoV-2. We saw a similar trend with the SARS outbreak in 2003, MERS in 2012 and one of the most devastating Ebola outbreaks in 2014. Especially with SARS and MERS, we knew little about these viruses, their transmission, incubation or natural course. Even Ebola, a disease first identified in 1976, raised questions about the appropriate level of protection As a result, the recommendations for personal protection equipment (PPE) and hygiene was evolving in real-time, with several changes throughout the course of these epidemics. Especially when recommendations change, hysteria and mistrust can ensue, among both laypersons and healthcare workers.

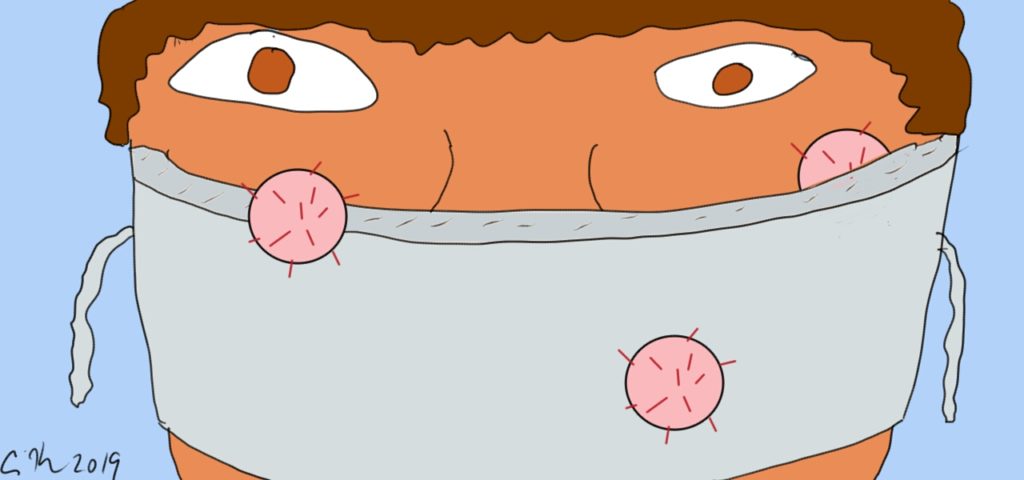

Currently, the guideline for healthcare workers for attending to patients with COVID-19 is the use of contact and respiratory precautions. This recommendation instructs healthcare providers to wear gloves, a fluid-impermeable gown as well as a mask with eye protection or a mask with goggles for routine patient care. The recommendations extend to the use of a PAPR, a powered air purifying respirator, for procedures that may produce an aerosol, like providing nebulized medications, intubating or suctioning. The face-mask guidelines are a little unclear, with some recommendations calling for a facemask with eye-shield and others requiring use of the N-95 mask.

There have been some interesting twists to the PPE saga. One is that the general lay public is turning to masks to help protect themselves from this virus. This is concerning for a couple of reasons. The first is that the supply of N95 masks, or any masks for that matter, is already limited. Hospitals here in the United States are scrambling for supplies and they are finding out that there are shortages worldwide. The manufacture of these masks is primarily in China, which has understandably halted exports for use in their own country. People buying up masks will only exacerbate this already critical shortage.

There have been some interesting twists to the PPE saga. One is that the general lay public is turning to masks to help protect themselves from this virus. This is concerning for a couple of reasons. The first is that the supply of N95 masks, or any masks for that matter, is already limited. Hospitals here in the United States are scrambling for supplies and they are finding out that there are shortages worldwide. The manufacture of these masks is primarily in China, which has understandably halted exports for use in their own country. People buying up masks will only exacerbate this already critical shortage.

The second is that experts have argued that the standard surgical mask is ineffective. Even if they offer some protection, they get contaminated easily and need to be changed regularly. Prolonged use of a single, disposable mask offers little to no protection. Even if a layperson gets their hands on an N95, they aren’t likely to be trained in its use or properly fitted. This is especially true for children and people with facial hair. The other measures we know to work, especially good hand-hygiene shouldn’t be replaced by the false sense of security a mask may provide.

It’s a tightrope though, because these are the very masks we are going to give patients and their loved ones if they come through the healthcare providers’ doors with COVID-19 , less to protect them and more to protect the others around them. We are going to give them the masks we just told them won’t protect them. We are going to give them a mask different from the one we are wearing and when they ask for our special mask, we will have to tell them “no”. These are tough conversations and few of us are prepared to answer why we can’t give them an N95, which they have surely read is the better mask.

As an additional consideration, the tradition of masks, particularly among the Asian population is centuries old and originated not to protect the wearer, but instead to protect people from the . It was a way for people who had symptoms to protect others and is rooted in their culture. The practice later morphed as a measure to protect against pollution and use now is likely a mixed bag of prevention, protection and even fashion. While this may have changed recently, suggesting that we change a cultural practice can be considered insensitive.

The answer for now can be something along the lines of discussing the shortages, that healthcare providers have far more and often closer contact with sick people and that other measures like keeping an appropriate distance from sick people (about 6 feet) and close attention to hand hygiene are, from what we currently know, effective measures. We also must realize that some people outside of healthcare should be trained to use and have access to an N95. This would include people who take care of sick loved ones at home. Most importantly, it is important that these recommendations from the top down, that in these times, when we are dealing with a new disease, information will evolve. We may increase recommended protections, or in some cases reduce them. Patients want and need to trust us and even a simple conversation about masks should be current, fact-based and honest.

My conversation, then, might go something like this:

Patient: “Excuse me,, can I get one of those masks?”

Me: “I’m sorry, these masks are for our staff, and quite frankly, there in a bit of short supply”

Patient:“But I saw you wearing one when you went into that patient’s room. If you are wearing one, why shouldn’t I”

Me:“This is a valid point, but these masks are specially fit, and we are trained in how to put them on and take them off. As a healthcare provider, I’m in close contact with people who may be sick, and this protects both of us”

Patient“But I see people wearing masks on the street, shouldn’t I be doing the same”

Me: “Also a good point. The fact is those masks don’t offer much protection. And the longer you wear them the less effective they are. The best defense is to wash your hands regularly, avoid people known to be sick if you can and avoid shaking hands and touching your face. These are measures we know to work and will help reduce your own personal risk. Masks might seem like a good idea, but they aren’t as effective as these simple steps.”

The patient may not be totally convinced but will understand. In times where we are preparing for crisis, we can’t afford to give people what they ask for just to be nice, or just to have good patient satisfaction scores. We need to resist, explain, and ultimately offer the best that science has to tell us.