by Craig Klugman, Ph.D.

Among other things, January is national mentoring month. And like much of academia in the midst of the hiring season, I recently sat in on a Skype Interview. In this version of the first-round interview, the institution has a faculty panel (and perhaps a student or two) asking questions of a candidate who may be across the hall or across the nation. When we finished the online conversation, my colleagues and I all agreed that the candidate, who has just received their doctoral degree, had not received good mentoring in how to approach an interview.

Jim Childress talks about the necessity of good mentoring in his 2007 chapter, Mentoring in Bioethics: “Based on gratitude, if nothing else, experienced and established bioethicists should feel an obligation to mentor newcomers to the field who may or may not be their own students.” We owe it to future bioethics scholars to help them because we received such support in launching our own careers: Pay it forward.

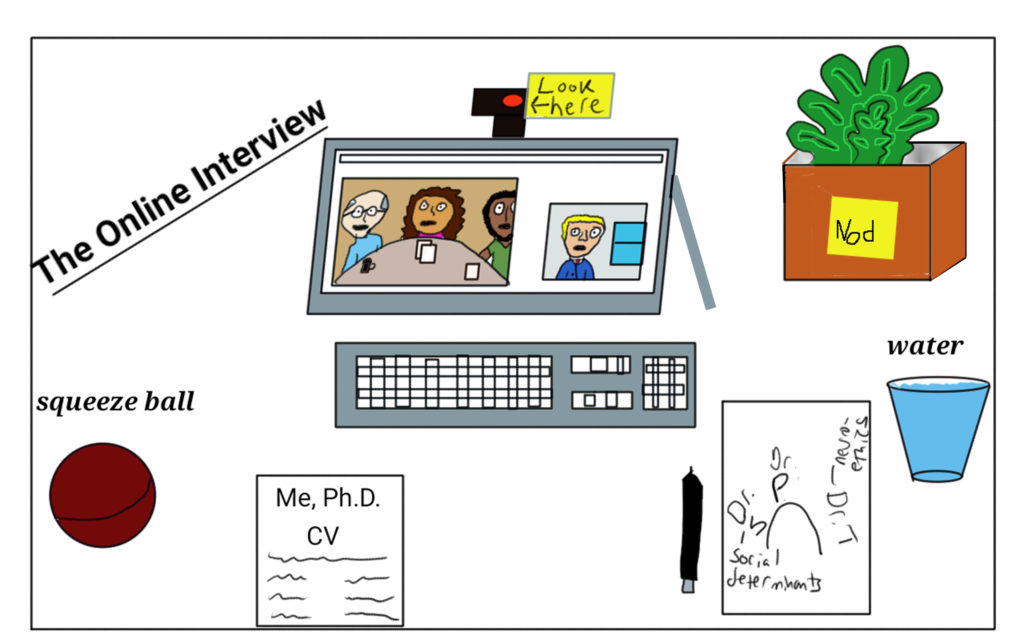

Thus, what I want to provide here is some advice that I wish the candidate we interviewed had received. Online interviews (Skype, FaceTime, Zoom) have become popular because they are inexpensive, time efficient, and allow a department to see how a person handles him or herself in real time.

- Be patient. When you first being the interview, everyone should check to be sure that video and audio is working well. If it is not, you may need to call back. If it is, then do not call attention the quality of the video or audio. If your connection is lost, then try calling back. Have a fully-charged phone handy and be sure that the interviewers have the number in case the tech does not work. I had one interview where the internet at my house went out just as the interview began. We were able to reconnect sporadically but eventually had to move to speaking on the phone. This worked well until my battery died and I could not complete the discussion. Needless to say, I was not offered a second-round interview.

- Make a map. I’m not great with names, so one of the first things I do when in any meeting is take a sheet of paper and draw an outline of a table. I then write down the name of each person and where they are sitting. This way, I can address people by name. I also take a few notes on something that person said, so I can write a personal element to my thank you notes. You may have been given a list of who will be in the interview beforehand—make sure you have looked them up. If you have not gotten such a list, you can request this information.

- Be aware of your body movements, especially nervous tics. Even though you are in a room by yourself, the interviews notice when you play with your hair, pick your nose, chew your headset cord, and rub your face. Your best bet is to sit on your hands or to have a paper and pencil and take notes. I have found that holding a squeeze ball with my hands under the table can help.

- Sit at a table and an upright chair. Perching your laptop on your knees in an easy chair while you speak to us means that the camera is constantly moving. As one of my colleagues said after our latest interview, “I felt dizzy because the camera kept bouncing up and down.”

- Be in a quiet space that you can control. I recall one interviewer who was in her cubicle in her shared grad student office. Not only could we hear the noise around her, but she had to stop talking to us to answer questions and even just tell people that she was busy.

- Dress as you would for an in-person interview. Yes, this means that you will likely be dressed better than the interviewers. Technically, you only need to “dress up” on the parts of you that will be seen in the camera, but being in a full outfit can make you feel that you are in the role of an interviewee rather than being in your home or your office.

- Think of the online interview as producing a theatrical scene. Ask someone to log onto Skype with you so that you can both see the scene. Are you sufficiently lit? One of our interviewees had bright light coming from a window behind him, which meant the camera was darkened and we could barely see the candidate. Make sure that your space on camera looks professional. Can you be heard clearly? You might want to use masking tape to mark what areas are on camera and which are off. Always practice.

- The nod. We cannot shake hands, so consider a simple nod. When each person on the interview introduces themselves, give them a brief and polite nod along with “Nice to meet you.” Similarly, you can use body language to let someone know that you are interested in what they are saying by offering the occasional head nod and tilting your head slightly to the right. These simple signals tell someone that you are engaged with that they are saying and you encourage them to speak more.

- Look at the camera, not the screen. This one is really hard, even for the interviewers. When you look at the screen, it appears that you are avoiding making eye contact. This is just how the technology works—the camera is often above the screen on a laptop. If your camera has a small light, aim to look at that, or stick a note next to the camera with an arrow. Yes, you might not be looking directly at the speaker, but we cannot tell that. If you look at the camera, then you are making eye contact.

- Do your research to know the institution. We ask candidates a few questions that are directed to see how much they know about our particular department and institution: Which of our existing classes could you teach? How does your research fit into the university’s mission? How would your interests fit in an interdisciplinary department? Given that I work at a teaching-oriented university, we want to be sure that the candidate is interested in us and understands what makes us a different place than a Tier 1 research institution.

- It’s not about you. In one case, we had a candidate who spoke only about what she would gain from being part of our department: I would be mentored by….I would learn so much from people in other disciplines…I learn a lot from my students.” Make sure that you touch on what you would contribute to your department. While there may be some professional mentoring, you are expected to arrive with at least the basic skills in running your own research projects, teaching a class, and participating in service. You are being hired for what you can do for us, not what we can do for you (not completely, anyway).

- Speak and then listen. In one interview, the candidate spoke, a lot. We actually started timing his answers because of how long they were. In one case, he spoke for 9 minutes without taking a breath. Yes, we are asking questions, but this is a conversation. This interview is not the time to show us how impressive you are; we saw that in your application packet. Speaking without pausing tells us that you might be a teacher who has a lecture-heavy style, rather than using active teaching methods. We are also thinking about sitting in a long faculty meeting with you, and wondering if you would be giving 9-minute speeches in that setting as well. Make your answers complete, but terse.

- Answer the question. When a politician is asked a question that he or she does not want to answer, the person will just ignore it and talk about what she wants to instead. That may work on the news but it does not work in a job interview. Listen to the question. Ask us to repeat it if you need. Answer all parts of it.

- Be specific in your responses. When we ask about your teaching or how you use students in your research, we are not only asking for your thoughts, we also want concrete examples. For example, “I believe that undergraduate students are insightful in that they often see things that those of us who are trained (i.e. have certain expectations) may not. I worked with this one student who was looking at a case and he saw….”

- Limit Drinking: You may have a glass of water nearby in case your throat dries up or you start coughing. But, you should try to limit drinking otherwise. Remember that Marco Rubio was mocked for drinking water during his Republican response to the State of the Union address. Taking a sip can look like you are stalling for time, not aware that you are being viewed by others, or lacking self control. If you truly need it, then of course drink up, but think about how others might perceive the action.

- Questions: I have never seen an interview that did not allow time for a candidate to ask questions. Express interest in the institution and the particular program/department. Take this seriously as we do keep track of what sorts of questions you come up with. Are the questions all about you personally? Do you ask about teaching loads and class sizes? Do you ask about research facilities available? Often, the interviewers see the questions you ask as an indication of where your interests and focus about that institution lay.

- Leave an open closing. At the end of the interview, the chair should explain the next steps in the process. If they do not, then you can ask.

- Always send a thank you email to everyone on the call. After the interview, compose a short email and send it to everyone who was part of the process. If you cannot remember their names, then send a thank you to the search chair and ask him/her for a list of who else was there so that you can send individual notes. You will need to look up their emails on the university website. I usually write a generic line “Thank you for taking the time to talk to me about the ______ position at ______.” I then add a specific comment that relates to that particular person. “I was very much taken by your description of the faculty as collaborative and student-focused as that describes my ideal work environment.” And then end with a generic, “I look forward to speaking with you further about my candidacy.”

While following these ideas will not guarantee you an on-campus interview, they will certainly help you to make a better first impression.