by Tyler S. Gibb, JD, PhD

Many news organizations have documented the horrific details of the crimes Larry Nassar, the disgraced former MSU and USGA gymnastic physician, committed against women and children over the course of his career (see, e.g., Indianapolis Star, Detroit Free Press, the New York Times, ESPN, and many more). I will not recount his crimes here but instead will focus on how he was permitted regular, unsupervised, intimate contact with so many victims, some children as young as 6 years old, even after victims complained about his actions.

…Because he was a physician.

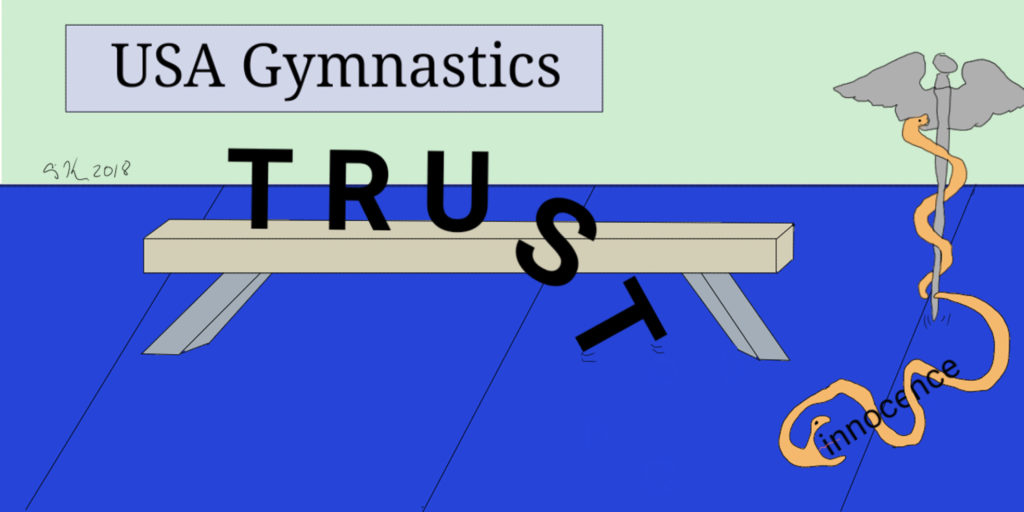

Despite a pattern of complaints of inappropriate behavior starting many years earlier, Nassar’s license to practice medicine in Michigan was revoked in April 2017. Both USA Gymnastics and Michigan State University were formally notified of concerns about Nassar’s behavior but failed to decisively intervene—allowing Nassar the opportunity to victimize more children. Investigations about the nature of these failures are on-going, but we can all expect the institutional repercussions to be significant beyond the resignations at higher levels that we have already seen. I am not alone in seeing the similarities between the Nassar-MSU situation and that of Jerry Sandusky at Penn State that captivated the country a few years ago. In both circumstances, institutions failed in their moral and legal duties to protect patients and minors from harm. If Sandusky’s crimes were repulsive because he leveraged his position as a coach, so much more repulsive are Nassar’s because of his role a physician.

As I teach professionalism and medical ethics to aspiring physicians, we often discuss the function of professional organizations and associations. Medical and Legal professional bodies grant permission to individuals to practice their craft within certain areas, generally states. But these guilds also have obligations that justify their social status and independence from governmental oversight. One of the required functions of a professional guild is to regulate its members. Colleagues (a derivation of the 16th-century French words that mean ‘to perform a task together) are obliged to look after each other and intervene when an individual’s actions threaten the reputation of the profession. Interventions are warranted in cases of addiction, mental health crises, misbehavior as well as incompetence. All professional guilds have formal reporting mechanisms and investigative bodies.

So, with the obligation to self-regulate and repeated complaints against Nassar, why did the medical profession not intercede? Part of the problem may be rooted in the two schools of medicine currently being taught and practiced in our country. The majority of US medical schools teach allopathy, whose graduates use MD after their names. The second type of training programs is osteopathy, connoted by the suffix DO. For the most part, the training programs are similar. Graduates of both schools must pass qualifying board exams and demonstrate competence in a specialty to be licensed. It is convention to refer to both allopathic and osteopathic physicians as ‘doctor’. The primary difference between allopathic and osteopathic training programs is the osteopathic training in manipulation treatment (OMT). This type of therapy involves physician using their hands to diagnose, treat, and prevent injury or illness through physical contact with various parts of the patient’s body. When I moved to a new city and established a care relationship with a physician recommended by a friend, I was surprised when he massaged, manipulated, and stretched me to assess my lower back pain. I could not have been more pleased with his expert care, but I admit that I was continually surprised by how much and where he touched me during examinations. Only later did I find out he was trained in osteopathy. Although I was not put off by osteopathic therapy, for some patients, OMT is uncomfortable and out of line with their preconceived expectations of how physicians should behave. Many MDs similarly are unfamiliar with OMT.

Nassar hid his criminal conduct under the guise of medical treatment. One of the most troubling statements to come out of this case is from another MSU coach who defnded Nassar by saying his actions were “a legitimate medical treatment.” How could any adult believe this to be the case? Physicians, we are taught from a young age, are worthy of our trust. We assume, as a matter of course, that physicians have our best interest at heart. There are certainly counter-intuitive aspects to modern medicine, but how could a reasonable adult interpret vaginal penetration to be a legitimate treatment for back pain? The answer is still confusing to many. The efficacy of osteopathy is evident, and in some cases, can complement or replace more invasive treatments. However, it seems clear that Nassar’s misuse of legitimate treatments—including Sacrotuberous Ligament Release—and the public’s unfamiliarity with osteopathy, in general, created enough uncertainty to allow for the abuse to continue.

In retrospect, it is easy to assume that Nassar’s behavior would have been unmistakably inappropriate to any parent, adult, or other physician in the room. But his carefully groomed reputation as a gifted healer of Olympic gold medalists, his powerful position as a physician and the attendant privilege to tell his victims, and others, that he was performing ‘legitimate treatment’ they were unfamiliar with, compounded the violence he inflicted. In our society, physicians are permitted to touch the bodies of their patients in ways that would be criminal in any other context. This privileged social status is justifiable only because of the benefit that physicians are able to provide to their ill or injured patients. Nassar was not only violating the bodies of his patients but was doing so under the mantle of medical care. The public trust of medicine—the body of caring, competent, professional healers—which the medical guild has a duty to protect, has also been considerably marred by Nassar’s crimes. Physicians, regardless of their training background, must be vigilant of their colleagues and better informed of different types of legitimate therapy. Just as the physician’s guild did in the late 19th century when they ran off snake oil salesmen and charlatans, physicians, both MDs and DOs must again decide what is legitimate medicine and who may enjoy the privilege of calling themselves a doctor. Internally regulating what is good medicine is not only the privilege of physicians, but is their moral duty. The failure to do so will further corrode the public’s trust in the noble profession, and continue to put us all at risk.