by Craig Klugman, Ph.D.

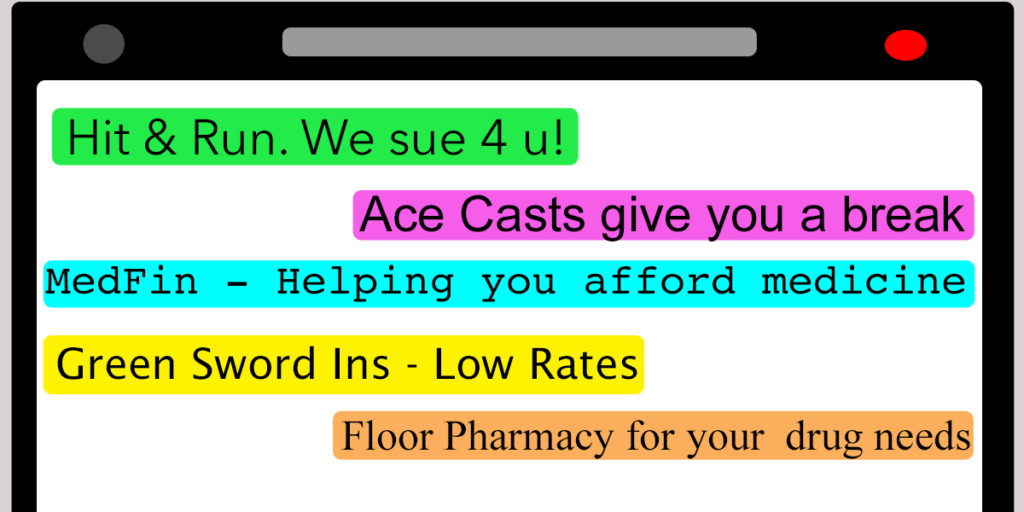

Imaging going to the doctor and suddenly finding ads popping up on your phone. Perhaps there’s a discount for receiving a specialized treatment. Another ad might advertise a vitamin or sunscreen. Or you might even get an ad for a competing service down the street. Targeted advertising is when a business or service sends its messages to people who meet a certain pre-determined demographic, in this case being in a certain geographic location. In the world of medicine, people used to receive ads for their diagnoses or other services at their health care provider because patient lists could be sold and used for marketing. HIPAA changed all that. As confidentiality and privacy rules were strengthened, your health information could no longer be sold for third-party marketing purposes.

But in adopting new technology, such advertising might be returning. No, HIPAA has not been weakened, but the ability to target has changed. No longer does an advertiser need to know that you are a dermatology patient or that you recently picked up a prescription for a certain condition. Now marketing allows for geographic tagging—your phone knows where you are and that data is readily available. When you go to the doctor or the hospital, your phone usually comes with you and the phone reports to your cell provider, the phone manufacturer, Facebook, Twitter, Google, and other services you have consented (often unknowingly) to track you. When you enter a certain vicinity, you may find yourself targeted for ads simply based on where you are standing.

This already happens in many stores. If you are part of a loyalty program or have downloaded the app for a store, you may receive electronic ads when you walk into the store or into a specific department. On entering housewares you may learn that there is a sale on toasters. The same technology and business model has now made its way into medicine.

An NPR story reported on apersonal injury law firm targeting people who entered a Philadelphia ER. The ads can appear for up to a month after your visit. In Massachusetts, a lawsuit against a Christian pregnancy and adoption center was filed after it sent targeted ads to people who visited Planned Parenthood.

Such programs do not violate HIPAA because they do not use private health information. However, that may simply mean that it is time to add geolocation to a list of HIPAA privacy elements. Such a need was evident a decade ago when I was working on ethical issues in rural health. If a patient’s car is seen in the doctor’s office’s driveway, neighbors may know who is inside. In a small town, people often know who drives what vehicle. In some rural offices, the doctor will share a parking lot with other businesses to give someone plausible deniability that they were at the office: “I was at the dry cleaners, not the doctor.”

Some apps have faced regulatory trouble when they have been discovered to be collecting unnecessary information. For example, a Facebook entertainment quiz famouslydownloaded much of a users’ personal information and that of their friends. The NPR article discussesa flashlight add that collected location information and sold that to advertisers. In both cases, public reaction was poor and regulators intervened.

While such targeted advertising may be legal, at the moment, the question is whether it is ethical. Certainly there is a violation of privacy if the patient has not given explicit consent to be tracked in this way. Though I am a big advocate for privacy, it is not an absolute and we do think about it on a spectrum. Tracking a person’s cell for medical advertising may feel unsavory, but the challenge of enabling geolocation on cell phones for 9-1-1 calls(basically EMS had no way of knowing from where a person called on their cell phone) led to outcry from public safety advocates. There is a convenience with walking into a market and being given a coupon for some item on sale. Many families use app services that allow you to track where other family members are at any time. My phone offers a reminder program that will remind you of a task or even when you reach a certain destination: I set a reminder so that when I get home, the phone messages me to water the lawn. When I recently was given a parking ticket saying that my car was in a particular area of town that I had never been to, I was able to use my phone’s GPS tracking log to show that I was nowhere near that location on that day. There are benefits to having geolocations on our phone.

The difference between the store coupon, knowing where my family is, receiving a reminder that I set, and having EMS locate me is that these are services I have opted into (or have not opted out of). Often when you download or initially use a program with location tracking, you have to agree to that feature (or you don’t get to use the software, so it may not be a real choice). But with the targeted advertising, I have not opted in to have my information shared. Thus, without informed consent and a vigorous opt-out/cancellation method, this is an ethical violation of privacy.

Another difference is that when walking into a store, I am usually not worried about my health. I am not in a vulnerable situation. Going into an ED, a hospital or a doctor’s office, even for a wellness checkup, means that I have some concern. These companies are targeting us with ads when we are at our most vulnerable. Even if given a chance to opt out or in, there may not be true consent because my rationality may be occupied elsewhere.

One could argue that I do not get to choose to receive television or radio ads—if you use those services then you listen to ads. But I do get to opt out of ads (pay stations, satellite radio) and I can always turn the devices off—they are not necessary for everyday living in the modern world. Turning off a phone in today’s world is as optional as choosing to turn off your home utilities (electricity and water). You can do it, but it will decrease your quality of life and ability to interact in the world.

The potential for targeted advertising urging us to purchase goods and services, to support certain candidates and issues in an election, or to have specific knowledge can cross a fine line between being for my benefit and trying to coerce me into doing something for someone else’s benefit. In some events, having the name of an attorney when in an ER after an accident might be helpful, but in these ads, I have no choice but to receive them. I suggest that we think about adding geolocation in a health care facility to be among define protected health information and that we consider how far we want to be tracked and geotargeted in our everyday lives.