by Craig Klugman, Ph.D.

One of my summer projects has been to undertake the most dreaded of adult tasks, updating my last will and testament and advance directive. Although I teach my students that everyone should have an advance care planning and end-of-life documents written in the state in which they reside, it has taken me 5 years to motivate myself to take my own advice. Although I teach my students that an advance directive should be reviewed and updated at least every five years (because when I have seen them challenged it is often on the basis that they are old—“Aunt Sally filled this out 15 years ago, she had no idea what her life would end up being like”), I have not updated mine in 10 years. Thus, I hired an attorney; my spouse and I made a visit to put together our documents.

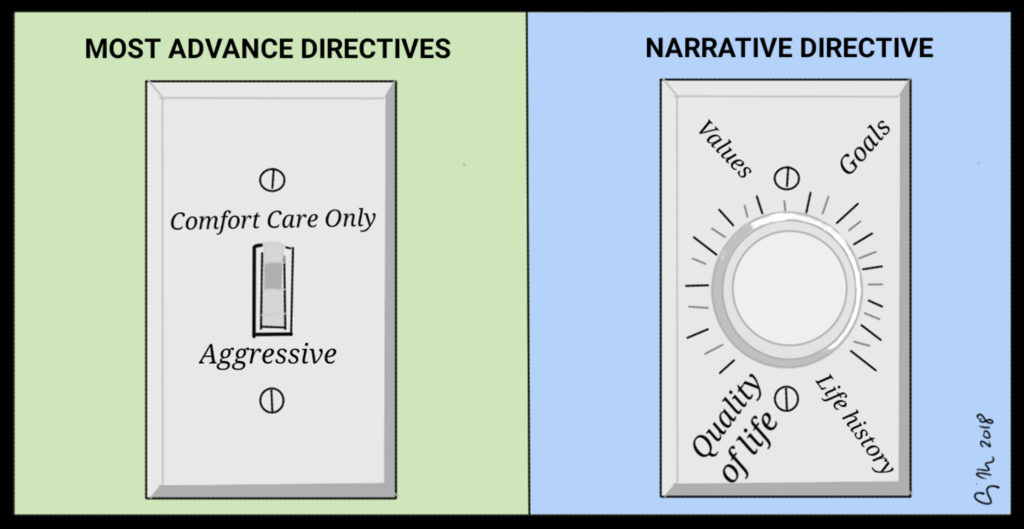

Many attorneys will commonly include an advance directive and medical-power-of-attorney as part of the package of writing a will. Like many law firms, this one had their own “standard” advance directive forms. Like the form listed on the State of Illinois website, this one was a check box of choose aggressive care or comfort care and listing a few names of surrogate decision-makers. Most law firms, states, and hospitals use a variation of this document. Sometimes there is an overarching choice and sometimes there is a choice depending on the scenario. For example, the state Illinois living will form offers

only one option: “Rejecting procedures which would only prolong the dying process be withheld or withdrawn, and that I be permitted to die naturally with only the administration of medication, sustenance, or the performance of any medical procedure deemed necessary by my attending physician to provide me with comfort care.” If you wish any other choice, then you do not complete this form (i.e. leave no instructions) or find another form. A directive should be about helping a person to make future decisions, not in forcing them to make any one particular choice.

The Illinois POLST is a little better, offering a selection of “Full Treatment: Primary goal of sustaining life by medically indicated means”, “Selective Treatment: Primary goal of treating medical conditions with selected medical measures” and “Comfort-Focused Treatment: Primary goal of maximizing comfort.” Like most forms, this one relies on making a singular choice—do everything (aggressive measures), do little (comfort care), or do something but not too much. This form is better than most in that it not only offers a list of choices, but also indicates what the goal of treatment is. However, POLSTS should only be used by those with a chronic or terminal illness, or who have reached a certain age where quality of life after a near-death event is likely to be significantly undesirable.

I explained to the attorney that as a 20-year-scholar of advance directives, I would prefer to find something more robust and frankly, more useful. I recalled a clinical ethics case we had a few years ago where an out-of-town patient arrived at the ED with an AD that focused on what to her was a quality of life worth living. Her daughter had the document and was supportive of decision-making that would follow her mother’s stated values. Although I have been involved with countless end-of-life decision-making cases, most without any advance directive, this particular statement was more useful than others. Instead of a simple choice of aggressive/comfort/something else, or a listing of procedures that we could/could not do that could not possibly have predicted the particular circumstances in which the person would find themselves, this one was more a guide to the patient’s values and life goals. The document talked about a quality of life as one that would leave the patient able to interact and communicate meaningfully with others, to be able to enjoy watching a sporting event, and to participate in her favorite activities (which were listed). Rather than wondering, “Would this patient really reject a vent if she knew that it was only temporary (a few days or weeks) and had a good chance of recovery”, we knew that the patient was open to treatments that would likely allow her to “actively play with her grandkids.” The consultants and physicians on the case all agreed that it was one of the most useful directives any of us had ever seen. Unfortunately, her condition was so compromised that medical science could not have left her in a state to meet her goals and threshold for a quality life. With the daughter’s agreement, we provided comfort care measures only.

As it turns out, such narrative directives are not all that common. In psychiatry, Ulysses contracts have been viewed in “a narrative perspective”, meaning that the patient’s stated wishes should be viewed in the context of their entire life values and choices rather than those made at one time or after a diagnosis of illness. Other articles have looked at advance care planning as a narrative. This approach looked at how successful advance care planning is done and suggests that it includes talking about “loved ones’ end-of-life narratives, hypothetical narratives, and constructed dialogue.”

With this experience and literature review in mind, I began to craft what I will call a “narrative directive.” Instead of a simple checklist, this one tells my story of what is important to me, what makes a quality of life, what procedures I would be inclined to receive and which would not match my goals. This directive not only provides a vision of my future self and decisions, but also gives the context from my past: Discussing what values and beliefs I have held over a substantial part of my lifespan—things like being a pescatarian (do not feed me the meat of mammals); being an atheist (keep any clergy from my bedside); and I do not want any procedure that merely prolongs my dying (see a 20-year-body of my writing to support this value). By talking about my past, the choices and goals I state for the future are grounded in my long-held values.

My directive offers five sections: (1) the situations in which I would want to be treated and in which I would not; (2) The conditions in which I want to kept (pain free, level of benefit, keeping my body supported long enough for family to say goodbye, altered status thoughts; co-morbidity thoughts); (3) What I value or what makes a life worth living (including being told the truth of my condition, even if not conscious; favorite activities); (4) spiritual comfort—none; (5) my thoughts on medical care; and (6) further thoughts—where I want to be, freedom from political harm, and protection from a rogue medical power of attorney (someone not making choices for me in line with the values and wishes stated in my document). The entire document is 3.5 pages and you can view an outline of it here.

I hope that I never need to find out if this document is effective. One creates an advance directive in the hope that it is never needed, but in the knowledge that there is no harm in being prepared. I wrote my directive in this format thinking about what would be most useful in ethics consulting on an end-of-life decision-making case. My goal is to help my loved ones and my health care team to more easily make a decision that they think I would have made, and to remove from their shoulders any guilt or uncertainty about the actions they take on my behalf. Although we sell these documents as helping a patient to maintain autonomy, I look at them as providing compassionate help to those who have to live with the decisions, and that is usually not the patient.